|

|

|

|

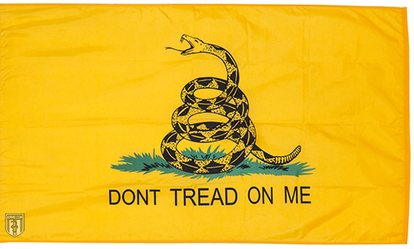

Don't Tread on Me

The history of the Gadsden flag and how the rattlesnake became a symbol of American independence by Chris Whitten, July 5, 2001, updated September 2002

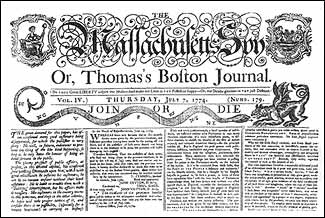

Don't Tread on MeThe Fourth of July never fails to reinspire my patriotism and sense of community with my fellow Americans, even when those fellow Americans are a mob of drunken cretins and teenagers trying to get out of downtown Chicago at 11pm. I like seeing all the American flags. I do have my complaints about the American government, especially about how intimately the Washington D.C. politicians feel they should be involved in the daily lives of their subjects, I mean, citizens. But the flag isn't just a symbol of the American government. It's a symbol of shared American values -- especially our highest common value: freedom. When it comes to symbolizing freedom and the spirit of '76, I do think there's a better American flag. With all due respect to the stars and stripes, I prefer the yellow Gadsden flag with the coiled rattlesnake and the defiant Don't Tread on Me motto. The meaning of Old Glory can get mixed up with the rights and wrongs of the perpetually new-and-improved government. The meaning of "Don't Tread on Me" is unmistakable. There's also an interesting history behind this flag. And it's intertwined with one of American history's most interesting personalities, Ben Franklin. American unity Benjamin Franklin is famous for his sense of humor. In 1751, he wrote a satirical commentary in his Pennsylvania Gazette suggesting that as a way to thank the Brits for their policy of sending convicted felons to America, American colonists should send rattlesnakes to England. Three years later, in 1754, he used a snake to illustrate another point. This time not so humorous. Franklin sketched, carved, and published the first known political cartoon in an American newspaper. It was the image of a snake cut into eight sections. The sections represented the individual colonies and the curves of the snake suggested the coastline. New England was combined into one section as the head of the snake. South Carolina was at the tail. Beneath the snake were the ominous words "Join, or Die." This had nothing to do with independence from Britain. It was a plea for unity in defending the colonies during the French and Indian War. It played off a common superstition of the time: a snake that had been cut into pieces could come back to life if you joined the sections together before sunset. The snake illustration was reprinted throughout the colonies. Dozens of newspapers from Massachusetts to South Carolina ran Franklin's sketch or some variation of it. For example, the Boston Gazette recreated the snake with the words "Unite and Conquer" coming from its mouth. I suppose the newspaper editors were hungry for graphic material, this being America's first political cartoon. Whatever the reason, Franklin's snake wiggled its way into American culture as an early symbol of a shared national identity. American independence The snake symbol came in handy ten years later, when Americans were again uniting against a common enemy. In 1765 the common enemy was the Stamp Act. The British decided that they needed more control over the colonies, and more importantly, they needed more money from the colonies. The Crown was loaded with debt from the French and Indian War. Why shouldn't the Americans -- "children planted by our care, nourished by our indulgence," as Charles Townshend of the House of Commons put it -- pay off England's debt? Colonel Isaac Barre, who had fought in the French and Indian War, responded that the colonies hadn't been planted by the care of the British government, they'd been established by people fleeing it. And the British government hadn't nourished the colonies, they'd flourished despite what the British government did and didn't do. In this speech, Barre referred to the colonists as "sons of liberty." In the following months and years, as we know, the Sons of Liberty became increasingly resentful of English interference. And as the tides of American public opinion moved closer and closer to rebellion, Franklin's disjointed snake continued to be used as symbol of American unity, and American independence. For example, in 1774 Paul Revere added it to the masthead of The Massachusetts Spy and showed the snake fighting a British dragon. The birth of the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Marine Corps [The seal from a 1778 $20 bill from Georgia. The financial backing for these bills was property seized from loyalists. The motto reads "Nemo me impune lacesset," i.e. "No one will provoke me with impunity."] By 1775, the snake symbol wasn't just being printed in newspapers. It was appearing all over the colonies ... on uniform buttons ... on paper money ... and of course, on banners and flags. The snake symbol morphed quite a bit during its rapid, widespread adoption. It wasn't cut up into pieces anymore. And it was usually shown as an American timber rattlesnake, not a generic serpent. We don't know for certain where, when, or by whom the familiar coiled rattlesnake was first used with the warning "Don't Tread on Me." We do know when it first entered the history books. In the fall of 1775, the British were occupying Boston and the young Continental Army was holed up in Cambridge, woefully short on arms and ammunition. At the Battle of Bunker Hill, Washington's troops had been so low on gunpowder that they were ordered "not to fire until you see the whites of their eyes." In October, a merchant ship called The Black Prince returned to Philadelphia from a voyage to England. On board were private letters to the Second Continental Congress that informed them that the British government was sending two ships to America loaded with arms and gunpowder for the British troops. Congress decided that General Washington needed those arms more than General Howe. A plan was hatched to capture the British cargo ships. They authorized the creation of a Continental Navy, starting with four ships. The frigate that carried the information from England, the Black Prince, was one of the four. It was purchased, converted to a man-of-war, and renamed the Alfred. To accompany the Navy on their first mission, Congress also authorized the mustering of five companies of Marines. The Alfred and its sailors and marines went on to achieve some of the most notable victories of the American Revolution. But that's not the story we're interested in here. What's particularly interesting for us is that some of the Marines that enlisted that month in Philadelphia were carrying drums painted yellow, emblazoned with a fierce rattlesnake, coiled and ready to strike, with thirteen rattles, and sporting the motto "Don't Tread on Me." Benjamin Franklin diverts an idle hour In December 1775, "An American Guesser" anonymously wrote to the Pennsylvania Journal: "I observed on one of the drums belonging to the marines now raising, there was painted a Rattle-Snake, with this modest motto under it, 'Don't tread on me.' As I know it is the custom to have some device on the arms of every country, I supposed this may have been intended for the arms of America."This anonymous writer, having "nothing to do with public affairs" and "in order to divert an idle hour," speculated on why a snake might be chosen as a symbol for America. First, it occurred to him that "the Rattle-Snake is found in no other quarter of the world besides America." The rattlesnake also has sharp eyes, and "may therefore be esteemed an emblem of vigilance." Furthermore, "She never begins an attack, nor, when once engaged, ever surrenders: She is therefore an emblem of magnanimity and true courage. ... she never wounds 'till she has generously given notice, even to her enemy, and cautioned him against the danger of treading on her."Finally, "I confess I was wholly at a loss what to make of the rattles, 'till I went back and counted them and found them just thirteen, exactly the number of the Colonies united in America; and I recollected too that this was the only part of the Snake which increased in numbers. ... "'Tis curious and amazing to observe how distinct and independent of each other the rattles of this animal are, and yet how firmly they are united together, so as never to be separated but by breaking them to pieces. One of those rattles singly, is incapable of producing sound, but the ringing of thirteen together, is sufficient to alarm the boldest man living."Many scholars now agree that this "American Guesser" was Benjamin Franklin. Franklin, of course, is also known for opposing the use of an eagle -- "a bird of bad moral character" -- as a national symbol. http://www.gadsden.info |

The Gadsden Flag: Don't Tread On MeIt’s hard to miss the Gadsden Flag these days.

Although it sprung back into popular American consciousness when the Tea Party first got its legs, this is a flag with a long and storied history. In fact, the flag is older than the United States itself. Back in 1751, Benjamin Franklin designed and published America’s first political cartoon. Called “Join Or Die,” it featured a generic snake cut into 13 parts. The imagery was clear: join together or be destroyed by British power. But why a snake? Around this time, Great Britain was sending criminals over to the colonies. Franklin once quipped that the colonists should thank them by sending over shipments of rattlesnakes. As American identity grew, so did an affinity for American (as opposed to British) symbols. Bald eagles, Native Americans and the American timber rattlesnake – the snake depicted on the flag. By the time 1775 rolled around, the rattlesnake was an immensely popular symbol of America. It could be found throughout the 13 colonies on everything from buttons and badges to paper money and flags. No longer was the snake cut into pieces. It was now recognizably the American timber rattlesnake, coiled into an attack position with 13 rattles on its tail. The flag takes on a special historical significance at the Battle of Bunker Hill. This battle, still celebrated in Boston, is where Colonel William Prescott famously gave the order not to fire “until you see the whites of their eyes.” One thing the battle underscored was that the Continental forces were woefully low on ammunition. In October of that year, the Continentals learned that two ships filled with weapons and gunpowder were headed for Boston. Four ships were commissioned into the Continental Navy, led by Commodore Esek Hopkins, ordered to get those cargo ships as their first mission. In addition to sailors, the ships carried marines, enlisted in Philadelphia. Their drummers had drums featuring the yellow of the Gadsden Flag with the now well-known snake emblazoned on top. It included the words “Don’t Tread On Me” – a now-famous motto with an uncertain origin. In December of 1775, “An Anonymous Guesser” wrote a letter to the Pennsylvania Journal. While the letter is anonymous, most scholars now agree that it was written by Benjamin Franklin. This letter suggested, “As I know it is the custom to have some device on the arms of every country, I supposed this may have been intended for the arms of America." Anonymous Franklin’s reasons for such were as follows:

But what of the man himself? Who was Gadsden? Christopher Gadsden was the designer of the flag. He’s known as “the Sam Adams of the South.” Both a soldier and a statesman, Gadsden was a founding member of South Carolina’s Sons of Liberty chapter. He served as a delegate to both the First and Second Continental Congresses. He left the Continental Congress in 1776 to serve as commander of the 1st South Carolina Regiment of the Continental Army. His legislative service continued in the Provincial Congress of South Carolina. And during the war, he was captured and served 42 weeks in solitary confinement after refusing to cut a deal with British expeditionary forces. After the war, his health was in poor shape, primarily due to his time spent in an old Spanish prison. Gadsden was elected to the position of governor for South Carolina, but declined the position due to his health. He remained in the state legislature until 1788 and voted to ratify the United States Constitution. He died in 1805 and is buried in Charlestown. The Gadsden Purchase in Arizona is named for his grandson, who was a diplomat. Today you can find the Gadsden Flag and its variations throughout the conservative, libertarian and patriotic movements. The Tea Party waved it during their Obamacare protests in 2009. This is what caught the government’s attention. A 2009 report from Missouri law enforcement called the Gadsden Flag “the most common symbol displayed by right-wing terrorist organizations.” That same year in Louisiana, a man was detained by police simply for having a “Don’t Tread on Me” bumper sticker on his vehicle. Christopher Cantwell and other libertarians have added the rattlesnake and “Don’t Tread On Me” legend to the distinctive black-and-yellow anarcho-capitalist flag. Over 250 years after its creation, the Gadsden Flag resonates because of its stark imagery and simple message. “Don’t Tread On Me” with a rattlesnake poised to attack says all that needs to be said. It is not an aggressive posture, but rather a defensive one. It says to anyone who would tread on the liberties of free people to think twice. While free people are peaceful, their patience is not endless. Next time you hoist this flag up, don a hat with its image or throw a Gadsden Flag sticker on your car – remember that you’re standing in a fine tradition that includes the first American Navy and Marines and the patriot after whom the flag is named. __________________________________________  Commodore Hopkins, portrait by C. Corbutt, 1776. Click here for a larger image. The Don't Tread on Me flag in this image appears to be a First Navy Jack. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division Commodore Hopkins, portrait by C. Corbutt, 1776. Click here for a larger image. The Don't Tread on Me flag in this image appears to be a First Navy Jack. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The Gadsden Flag's Namesake

Rattlesnake Symbol | Gadsden Flag History | Christopher Gadsden | Culpeper Flag Christopher Gadsden & Esek Hopkins Although Benjamin Franklin helped create the American rattlesnake symbol, his name isn't generally attached to the rattlesnake flag. The yellow "don't tread on me" standard is usually called a Gadsden flag, for Colonel Christopher Gadsden, or less commonly, a Hopkins flag, for Commodore Esek Hopkins. These two individuals were mulling about Philadelphia at the same time, making important contributions to American history and the history of the rattlesnake flag. Christopher Gadsden was an American patriot if ever there was one. He led Sons of Liberty in South Carolina starting in 1765, and was later made a colonel in the Continental Army. In 1775 he was in Philadelphia representing his home state in the Continental Congress. He was also one of three members of the Marine Committee who decided to outfit and man the Alfred and its sister ships. Commodore Hopkins, portrait by C. Corbutt, 1776. Click here for a larger image. The Don't Tread on Me flag in this image appears to be a First Navy Jack. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Gadsden and Congress chose a Rhode Island man, Esek Hopkins, as the commander-in-chief of the Navy. The flag that Hopkins used as his personal standard on the Alfred is the one we would now recognize. It's likely that John Paul Jones, as the first lieutenant on the Alfred, ran it up the gaff. It's generally accepted that Hopkins' flag was presented to him by Christopher Gadsden, who felt it was especially important for the commodore to have a distinctive personal standard. Gadsden also presented a copy of this flag to his state legislature in Charleston. This is recorded in the South Carolina congressional journals: "Col. Gadsden presented to the Congress an elegant standard, such as is to be used by the commander in chief of the American navy; being a yellow field, with a lively representation of a rattle-snake in the middle, in the attitude of going to strike, and these words underneath, "Don't Tread on Me!" This history of the Gadsden flag was written by me, Chris Whitten, based on extensive personal research. It also appears on FoundingFathers.info. http://www.gadsden.info ______________________________________

The Culpeper Flag

Flag of the Culpeper Minute Men. The Gadsden flag and other rattlesnake flags were widely used during the American Revolution. There was no standard American flag at the time, not even Betsy Ross's stars and stripes. People were free to choose their own banners. The Minutemen of Culpeper County, Virginia, chose a flag that looks generally like the Gadsden flag, but also includes the famous words of the man who organized the Virginia militia, Patrick Henry: "Liberty or Death." By the way, there's a fair amount of confusion about the spelling of Culpeper. You often see it spelled Culpepper, with three p's. These are both, legitimate alternate spellings of an English surname. But the flag should definitely be spelled Culpeper, since that's the official spelling of Culpeper, Virginia. Note: This history of the Gadsden flag was written by me, Chris Whitten, based on extensive personal research. It also appears on FoundingFathers.info. http://www.gadsden.info __________________________________________ |